The Two Cultures and the Engineering Revolution

Risk, shiny objects, speed, and ego: notes from the valley of a cultural divide.

Contents:

Origins of observations on a cultural divide

Over the past ten or twelve years, I’ve had the privilege of working on a varied and often incredibly interesting set of problems. The products I’ve helped push forward, however far my efforts actually got us, range from exotic internal combustion engines to data-hungry, data-spewing financial analytics systems†.

Whatever the product or the high-level objective, however, the professional worlds I have inhabited broadly fall into two camps, and I’ve spent about as long in each. Almost without exception, the teams I have worked in could be labelled as either mechanical engineering or as software engineering.

My experience of these worlds isn’t necessarily characterised by the work I actually carried out within them. Even when my job was to help design and develop racing cars, I still spent the majority of my time writing software… but the culture of those organisations would likely be alien to most modern software engineers, just as the culture of a software startup would likely be alien to most mechanical engineers.

Sit a software developer next to an aerothermal engineer at a dinner table otherwise occupied by non-STEM folks, and they will probably bond over their overlapping interests. But, look a little closer at their disciplines’ attitudes to work, and you’ll find a cultural fissure that’s harder to bridge.

Where I find this divide can cause the most friction is where they meet: engineering software.

† This is not an exhaustive list. About half my career has been spent building simulation and analysis tools for the motorsport world, developing engines and suspension systems, a smidge of mechanical design, and doing a bunch of DSP work for ECG processing - some of which apparently might now live in your smart watch. The other half has been spent building B2B SaaS software, including quantitative financial analytics products, engineering collaboration tooling, and LLM systems for the defence space.

On ballistics and divergence from an extant ancestor

One thing that often irks me about interdisciplinary rivalries is that the engineers who shape our digital world are drawn from exactly the same talent pool as those who shape our physical world. We are the same people. The best mechanical engineers I’ve worked with could be the best software engineers, given time and training and interest, and vice versa. Some of the best software engineers I’ve worked with have had electrical and electronic engineering degrees.

Today, computing is its own discipline, complete with its own formal methods and class of thought, but its origins are in the service of engineering.

The history of the two worlds is also fundamentally intertwined. The computer basically exists to meet the needs of engineers. Charles Babbage’s difference engine was brought into being to produce trig and log tables. A century or so later, the first ‘modern’ digital computer was designed and developed for the United States Army Ordnance Corps to perform ballistics calcs. Recycling my own scribbling from a few years ago:

Fast forward to 1945, and we see the first glimpse of modernity: ENIAC, the world’s first programmable, electronic, general-purpose digital computer. If you’re curious as to what was it designed for, the answer is the computation of artillery and mortar firing tables; a task that involves exactly the kind of Newtonian mechanics calculations that will be familiar to any undergraduate mechanical or aerospace engineering student (see: Mayevski’s Traité de balistique extérieure , or the US Army Ballistic Research Laboratories’ The Production of Firing Tables for Cannon Artillery).

Engineer demand shaped early computation because it was an attractive tool with applications across engineering domains; nobody in the 1950s wanted a computer to run photo sharing or restaurant booking applications. The people who wanted access to compute were working on problems in ballistics, nuclear weapons and nuclear energy, fluid dynamics, and solid mechanics.

Engineers also played a role beyond simply forming the demand for better tools. While many of the founding figures of what we now call computer science were mathematicians and logicians, like Alan Turing and John von Neumann, many of the space’s pioneers were also qualified electrical engineers: Vannevar Bush, Claude Shannon, John Eckert, Jack Kilby, John Atanasoff.

I say this to highlight that computer science existing as a distinct discipline is an incredibly recent development. The architects of the computing revolution were often solving real, physical engineering problems which we would recognise as belonging to the school of electrical engineering—and the discipline’s fragmentation from the rest of the engineering faculty occurred within living memory.

Contrast and critique

My experience leads me to the conclusion that the two cultures, which I will generally call here engineering and software, could each stand to learn a good deal from the other†. In many cases, the differences in outlook can be rationally explained… but in others, I feel that the differences in stance can be attributed to groupthink at best, and a quasi-sectarian belief system at worst.

Looking to four traits and how they compare between camps…

† This split in categorisation is reductive, but carries for the point I'm trying to make. There's no judgement from my end over who does and doesn't deserve the 'engineer' title; designing and developing software systems scratches the same part of my brain as designing and developing hydropneumatic suspension systems did.

Risk

Differences in attitude to technical risk are, I think, driven by engrained domain-specific perceptions of the cost of failure. Of course, there are extremes in both cases, and I’ve certainly met MISRA C extremists who are more risk averse than people making low-cost attritable drones, but the sense I have for each culture probably maps to its median member.

In most modern software that’s delivered over the internet, the cost of failure generally rounds to zero. If you make a mistake, you just fix it as soon as possible and deploy the fix to your users immediately. It may be damaging to customer trust if you do this a lot, but it doesn’t generally cost you anything to actually have your patched product make it to them. Having this even be an option allows for a trade-off that simply isn’t available in most walks of life: you can tackle projects one small bite at a time, while also letting your customers make use of every incremental upgrade.

However, if you are developing planes or cars or kitchen mixers, things are a very different. If a car makes it to market with a flawed water pump design, and several hundred thousand models are sold before the issue becomes apparent, you cannot push a hotfix and wait a few minutes as that rolls out to the customers. The economic cost and logistical complexity of a recall is, I suspect, not readily intuited by the architects of our digital world.

For example, in 2009/2010, Toyota recalled 9 million vehicles for issues with accelerator pedals and hybrid ABS systems. Unlike in software, once you have identified the issue and established a fix, the cost of getting that fix to the customers is decidedly non-zero. Analysts from UBS estimated this round of recalls was likely to cost around $900 million, while Toyota also reached a $1.2 billion settlement with the DOJ for its handling of the issue.

Given these respective costs, the cultures have adopted opposed but rational positions. Aerospace and automotive engineering teams are acutely aware that the cost of making a mistake could be astronomical. Not only could you cost your company billions of dollars through a design flaw, you could also quite readily kill someone.

While this is also true of some software teams, I don’t think it is true of most. If someone ships a bug to the users of Steam or Figma, nobody’s life is at risk and it’s not very likely to cost them $2 billion. If it’s important, they can fix it quickly, and maybe even win some customer affection by handling it well: responding to the report quickly, being helpful, and fixing the issue right away.

The result of all this is that engineering people are typically markedly more risk averse than their software people counterparts. In many respects this makes sense. Slow progress in software can form an existential threat to a business, just like a design flaw in a physical product—but that design flaw could actually cost lives as well.

On the acceptance of design defects

I suspect this emerges from the differing costs of failure between disciplines, but software culture treating ‘bugs’ as unavoidable and near-organic issues in the development of their systems, in my mind, is a cultural flaw. Your bug is not a moth trapped in a relay; it’s a defect in the design and implementation of your system. Bugs are too often brushed off, and should be treated like more serious engineering faults, particularly for systems where the impact of an issue could be severe.

Shiny objects

With respect to the adoption of new technology, or even the openness to it, I think we see the divergent costs of failure raise their heads once more.

Engineering culture values proven, battle-tested techniques. Because the cost of failure is high in this world, it values stability and reliability, sometimes at the expense of capability and productivity.

Software culture, on the other hand, values novelty and progress, sometimes at the expense of stability and reliability. Because the cost of failure is low in this world, it values incremental advances and product forks and modern conveniences. Unfortunately, it can also be prone to chronological snobbery; assuming that a given tool or product or technology is somehow inferior purely by virtue of its age.

As best as I can see, the software world actually benefits a great deal from the compounding effect of incremental advancement and rapid turnover of its chosen tools. The tools we write software with are getting better all of the time, and we get more productive as a result. If you can manage a 10% improvement in productivity every year, that’s a 2.6x improvement over a decade.

Conversely, many engineering software packages are slow-moving giants. The capability they offer may be incredible, and they may be significantly more complex systems, but there is little in the way of exponentiating improvement from the biggest players. While there may be good technical justification for this, it is also the case that the customer generally wants stable, proven solutions, so there is little demand-side pressure for any kind of iterative and fast-moving approach.

Speed

Diverging attitudes to pace of development are fascinating to me. Both Kelly Johnson and Ben Rich’s books on Lockheed talk at length about a focus on fast, simple processes and small, elite teams. These were pursued, at least in part, because they allowed for new aircraft to be developed extremely quickly.

Today, however, I think you would be more likely to find that sort of ruthless dedication to speed and performance in a software team. The relative lack of regulatory burden in the software space may have something to do with this, allowing teams to hit the throttle, while also attracting the sort of engineer who wants to hit the throttle, but I think it is also cultural.

Speed and urgency are critically important to startups, and many of the cultural heavyweights of the technical world really are (or were) startups, from Google and Facebook to Amazon and Stripe—and I think the cultural ripple effect from these companies has been large enough to influence the space more widely.

On the contrary, I suspect most mechanical and aerospace teams today are probably no quicker at bringing new systems to market today than they were four or five decades ago. Today’s engineered systems are, obviously, significantly higher quality than their antecedents, so there is ultimately more work to do to make it to production—but I also suspect that the median hardware team has a less urgency-focused culture than the median software team.

Practically, this may just be another manifestation of relative risk appetite, but you can see it in the tools and processes adopted by each team. A software team working with a tidy continuous delivery process are likely shipping updates to their customers several times per day. A single colleague approving a PR is often enough sign-off for new features to make it to the deployment process, and both GitLab and Google have entire teams focused on engineering productivity.

Contrast this with the stage-gated design review process, drawing reviews, ECRs/ECNs/ECOs, and certifications demanded in the typical mechanical workflow. I even once met with a team of very obviously high-capability engineers working on a widely used aerospace product who said it typically took them several weeks to get finalised designs released.

Perhaps this pace is driven by the desire to avoid a recall or a catastrophic accident, but I cannot imagine Kelly Johnson would have thought highly of it.

Release cadence and regulated environments

Software products intended for use by tightly regulated industries are often subject to relatively lengthy certification procedures and, as a result, updated infrequently. For example, if you’re writing embedded software for a commercial aircraft system with Simulink, that version of Simulink Coder will likely have gone through some variety of DO-330 Tool Qualification procedure.

Even without regulatory imperative, ’technical baseline’ management and tracking may be imposed. NASA has run a CFD validation programme since the 1980s. When an upgrade is available, it isn’t automatically rolled out to the user base; it’s validated against some prior version in an attempt to ensure there has been no unintended regression in functionality, and this goes through some kind of formal change control process.

These seemingly conservative, bureaucratic approaches to things arise from a very legitimate desire not to kill anyone. Whatever their cause, however, they do exist, and they will mean that some teams are somewhat uncomfortable about not really being in control of the software versions that they run. This is a bit of a conflict between the norms in these two spheres, and means that many people from a modern software background attempting to engage with these teams will have to come to grips with a slower and more paperwork heavy approach to application updates.

Ego

I think all technical fields probably overestimate how complicated and useful their work is, and underestimate how complicated and useful everyone else’s is. However, in this case, I think there’s a slight difference in how these fields view both themselves and one another.

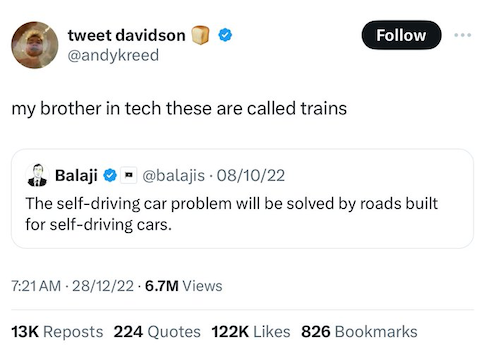

Engineering people think that software is not really engineering; that modern software development is shuffling buttons around and gluing libraries together in service of frivolous goals. If you’re designing modernity’s remarkably efficient jet engines or developing new medical devices that might actually save lives, that certainly feels more meaningful than working on the next AirBnB for Cats or an iPhone app that mimics the act of drinking a glass of beer.

Software people, on the other hand, look down their nose at engineering, as if it’s some staid and primitive craft in dire need of their ‘disruption’. It’s old men in smart-casual office wear, pedalling giant spreadsheets and throwing shit together in some ugly CAD system—and on Windows too, eww. Obviously, these people could never grasp the scale of intellect required to daily-drive Arch and Neovim, never mind appreciate the finer points of Hindley-Milner type inference or why Haskell is better than OCaml.

Anyone who recognises themselves in either of these positions is wrong, and both views are counterproductive.

For the engineering people, specialised software has already offered revolutionary advances in capability. Without modern CAD, FEA, CFD, MBS etc., we would not be able to build today’s machines. But, I still think that both the design office and the shop floor are problem-rich environments, and I still think that software has a lot of potential to make things better.

Yet, resistance to more software is something I have found to be relatively commonplace, even if sometimes with good reason. Engineers who want to design cars and machinists who want to cut metal are generally invested in the tools they use already; engineering software is often incredibly complex, expensive, and hard to get to grips with, so almost nobody bothers to look around to see what tools are out there. Software can almost certainly help you do a better job, but not if you treat your existing tool or process selections as utterly sacrosanct.

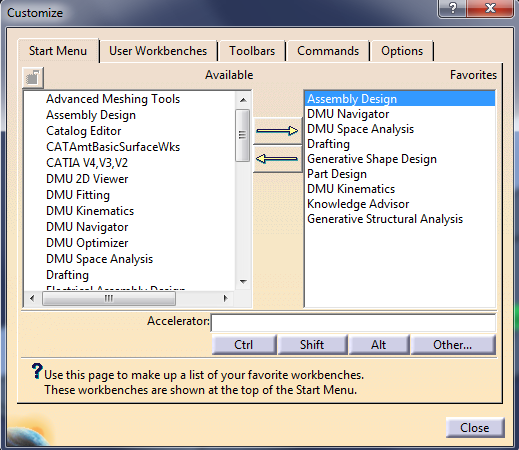

Credit: https://catiav5v6tutorials.com/how-to/create-rapid-links-to-most-used-catia-modules/

For the software people, assuming you work on systems for paying business customers, your job is entirely about building tools to help other people do their jobs. To the customer, you are no different to the people who supply screws or coffee cups; you offer a cog for a large machine whose purpose is to make money.

Despite this, software people have a reputation for hubris and overconfidence and reinventing things as old as time; for thinking that they have untangled the secrets of the universe, and that nobody else can hold a candle to their brilliance. That hubris is almost always bad. Your customer cares almost exclusively about the capability of the product; they do not care how clever you are, and they do not care at all about your choice of tech stack. The programming language or paradigm you have adopted matters to them only if it has a material impact on the product’s capability and reliability, and they care only about the capability and reliability—not how it was achieved.

Consequences

With respect to the intersection of these worlds, the engineering software space, the result of this division is effectively a loss for both sides.

Inertia and opportunity cost

Engineering’s culture of risk aversion is, I think, one of the reasons why engineering software is so ‘sticky’ and has such high inertia. While concerns about new tool adoption can be justified, this is partly the cultural bleed-over from the more physical work. Engineers don’t want to change things because they’ve pattern-matched to the idea that if something goes wrong, it could be extremely costly. Nobody wants to hitch themselves to a new simulation tool, trust its output, then find that they are ultimately responsible for a wall collapsing or a control arm breaking—no matter how unlikely.

However, if engineers had always held this position, they would have never stopped using slide rules or adopted software systems in the first place. New tools, suitably stress tested, can still improve things. By not being as open minded as their software counterparts, engineers lose out on the possibility of developing better products, of bringing them to market faster, and of getting to use exponentially improving tools that they might love.

The innovation gap

The software world is, I think, more open to new ideas and new tools than the engineering world. It develops and adopts new products more readily, and it is more willing to try new things.

However, the space also readily falls for an appeal to novelty. This collides with the engineering world’s demand for battle-hardened, ultra-reliable systems, which itself engenders a scepticism of anything new and unfamiliar.

In the end, genuinely novel and valuable engineering technology may get lost in the middle.

Cadence mismatch

An unfortunate consequence of the certification process for new tools, internal or otherwise, is that upgrades often have to come in lumps, and they require more effort to introduce.

However, as much as slick, continuously upgraded applications that are served over the internet may be great for rapid improvement of the product, and for the customers who want bleeding edge functionality, they might not be great for those customers whose primary objective is the avoidance of a multi-billion dollar lawsuit and/or recall programme.

If you can’t provide the capacity to re-run some FEA as part of safety-critical stress work using exactly the same solver and data versions, that may well be unacceptable. The consequence here is that both sides lose unless they adapt to one another; shipping fast doesn’t help if your customer can’t make use of the output.

The destructive nature of mutual contempt

Irrespective of origin, conflict forms a feedback loop. If engineering people see software people as arrogant cowboys and software people see engineering people as mentally inelastic Luddites, neither will listen to the other, and both sides will lose. Any hint of mutual contempt destroys the opportunity for mutually beneficial collaboration.

As someone who enjoys building software tools for engineers, this saddens me.

Where do we go from here?

My (wholly unsolicited) take on what the respective disciplines might do to close the gap and improve their own lives:

For teams developing physical products

- Process velocity: Where safety allows, try to pilot modern tooling. Try to implement lightweight review loops and release processes to shorten iteration time as much as possible. Let the computer do the work.

- Tool-chain reviews: Periodically reassess software toolchain; legacy system stability/reliability should be weighed against possible advances in accuracy, productivity, or cost.

- Attitude: Your software colleagues have moved so quickly over the past twenty years that they might have some good ideas on how to do things. They can almost certainly help your teams be happier and more productive by improving how they work, and by providing upgraded tooling; they’re worth listening to.

For teams developing software products

- Bugs: Bugs constitute design defects and are engineering failures, and should be treated with the same formality applied to non-conformances in hardware.

- Customer and workflow sympathy: Consider offering long-term-support (LTS) tracks, version options, reproducible

builds and explicit sunset timelines; these align better with regulated or safety-critical users than continuous,

non-consensual updates.

- On release cadence: Certification and baseline-control mean that some engineering organisations can absorb only infrequent, well-documented upgrades. Product road-maps should offer a channel that reflects this constraint.

- Attitude: A superiority complex is not a sales strategy. Your cousins from the physical world may actually know what they’re doing; please consider their needs. Approach them as equals with different priorities and they’re more likely to let you try to help.

For all sides

- Desks on wheels: Cross-functional teams and forward-deployed engineers can be very effective. Bring your engineers together.

Conclusion

The divide between these two cultures is not fixed. When I’ve seen mechanical teams and software teams work together, it’s obvious that they have much more in common than that separates them.

However, in the context of engineering software, neither camp has the luxury of ignoring the other’s priorities or constraints, and both could stand to gain from observing the other’s approach to their craft. Treating speed, stability, and safety, and whatever else they disagree on, as design variables that exist on some continuum, and not as disciplinary axioms, will make life easier for everyone.