Building a palatable 3D viewer | Part I

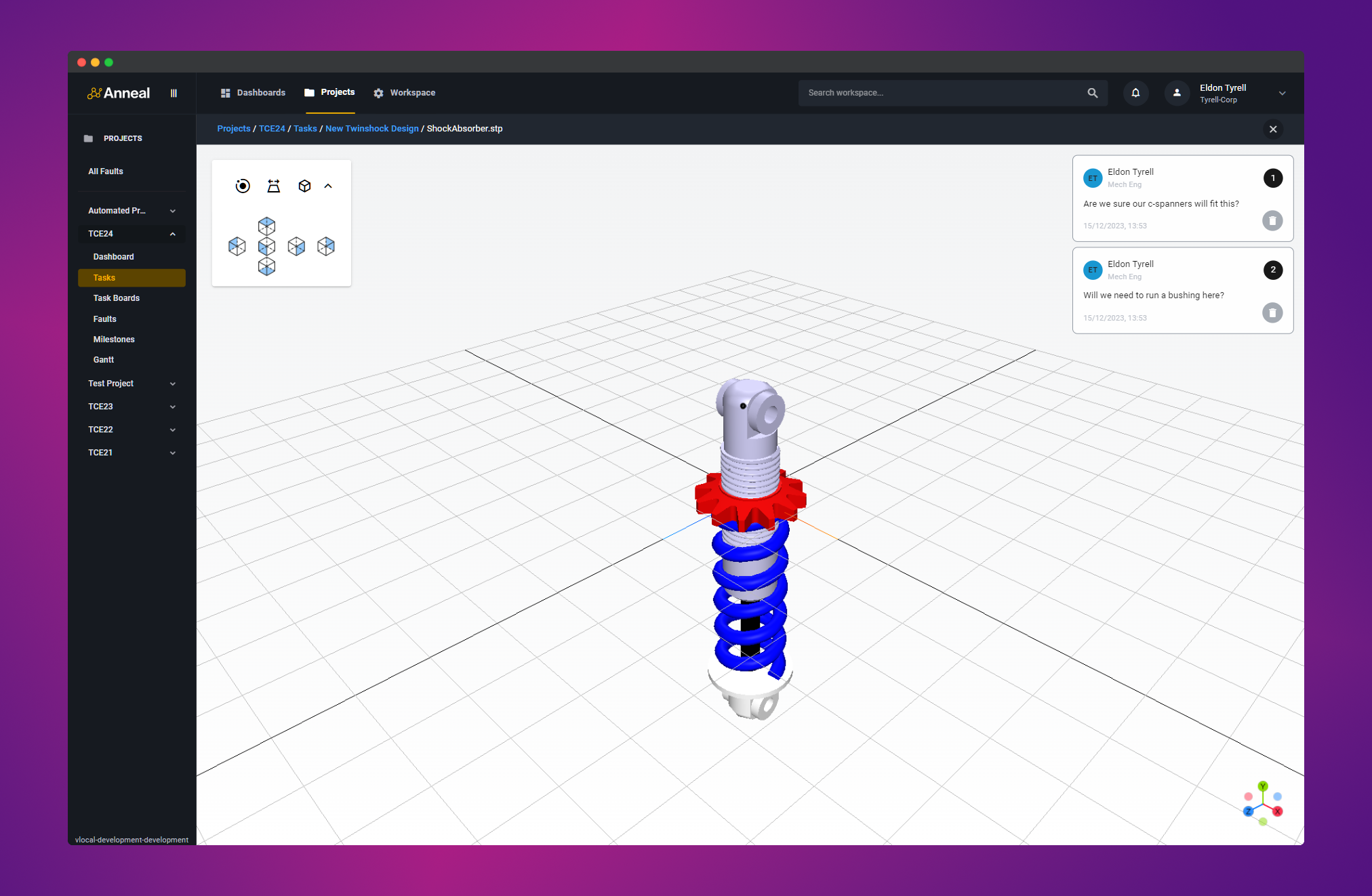

Engineering review procedures and using Three.js to visualise 3D CAD data.

Contents:

https://www.getanneal.com

Motivation: design reviews suck

The need to tackle this came from wanting to visualise 3D CAD data in a web browser, all as part of Anneal’s design review tooling.

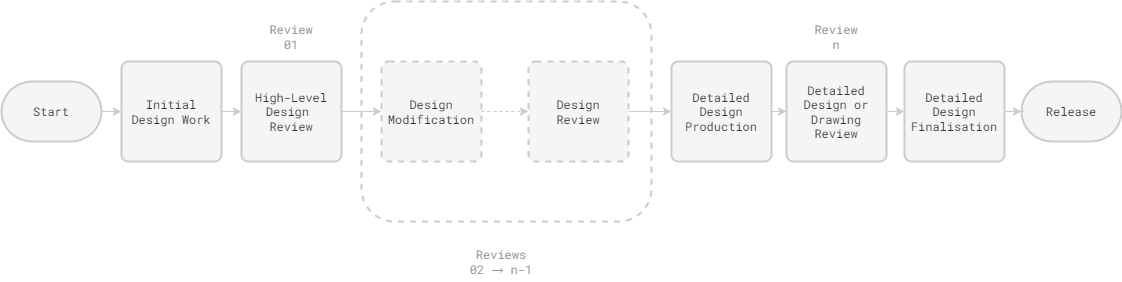

The general background is that engineering teams typically do—and are in many cases obligated to—perform some variety of stage-gated review process for new designs and design modifications. At one end, you might have a high-level concept review, and at the other, a detailed drawing review. The first allows the team to opine on design philosophy and direction, and the last serves to get more sets of eyes on things like GD&T on fully fleshed-out, detailed designs.

If you don't care about engineering procedure, you can skip this bit...

To illustrate, that process might look something like this:

So, the flowchart looks fine; no issues there. Unfortunately, the actual, practical processes followed by engineering teams are often archaic, unwieldy, untraceable, and error prone. Ignoring the drawing component, which—where it remains—is obviously 2D, the process of reviewing 3D designs tends to take one of the following forms:

Option A: The meeting room

This involves getting some people in the same room, preferably in front of a projector screen, such that a designer can twirl a model around in front them. While this happens, the assembled group try to make sense of what they’re looking at, and may occasionally chirp up with their thoughts on the design. If you’re lucky, the designer will have prepared some slides, and if you’re even luckier, somebody will be taking minutes.

Pros

- Quick and easy to arrange—just go and sit in a room and talk it out.

- No need to worry about file formats, or how to get the data into the room… unless you don’t have a laptop.

- Interactive, and allows for a degree of back-and-forth that can be hard to replicate with remote/asynchronous processes.

Cons

- Still some vulnerability to temperamental equipment; we’ve all been in meetings held up by uncooperative projectors.

- No real record of the meeting, and no way to trace the evolution of the design—unless your team is hot on keeping good meeting minutes. (They aren’t; they’re too busy.)

- Requires everyone to be in the office, and many teams have not yet returned to the office full-time.

- No real context for recording contributions; how do you verbally describe a particular feature or point in three-dimensional space where you see an issue or an opportunity?

- No way to share the detailed commentary with people who aren’t in the room, or who can’t make the meeting.

- Incredibly easy to get sidetracked.

- More reserved participants may not feel comfortable speaking up in a group setting, and may not be able to articulate their thoughts in the moment.

- Less reserved participants may dominate the conversation, and may speak up before they’ve really considered what they’re looking at.

- Potential for groupthink to set in, and for the team to miss something important.

For small, agile teams where traceability isn’t a big concern, I think this actually makes the most sense. If you’re working on simple components in a domain you all understand and you can trust your colleagues to be competent and diligent, then this can work just fine.

However, if your team is remote, big, working on anything complex, working on anything regulated or important, or even just wants to be able to look back on the evolution of a design, then this is already a poor choice.

Option B: PowerPoint e-mail ping-pong

This involves a designer taking screenshots of their CAD system and pasting them into a PowerPoint presentation—or maybe a Google Doc, if you’re lucky.

By collating some salient views of the design, perhaps annotating them, and then sending them around to the team, the designer can get try and elicit some feedback from their team.

Pros

- You don’t have to leave your desk, and providing you can operate PowerPoint, don’t even need to learn any new software.

- Going asynchronous forces the designer to think about what they’re sending out, and to try and anticipate questions and concerns. The PowerPoint becomes a guided introduction to the design.

- Caters to the needs of remote teams.

Cons

- The design is not shared in 3D, limiting comprehension and depth of understanding, and preventing interaction and exploration.

- Visibility is restricted to only the views and features the designer has thought pertinent.

- Feedback requires circulating the document via e-mail and waiting for responses.

- If this process involves four or five people, especially for truly single-player PowerPoint workflows, the designer must wait for all of these responses, then piece together the feedback from several e-mails and individual documents into some collated, actionable list.

- Unbeknownst to one another, contributors may cover the same ground in parallel, suggesting similar or identical changes to the design without the opportunity to actually discuss those changes in context.

- For the designer, the admin penalty from all this is high, and the process is slow and painful.

- Version control is a nightmare. Which version of the design was this feedback for? Which version of the PowerPoint was the feedback for that model version in? Which one’s the latest? Which one’s the one we’re working on now?

- Traceability sucks. Reviewing the design’s evolution, even months later, involves piecing together the narrative

from scattered, asynchronous e-mail conversations.

- Teams may get around this by dragging the e-mails into a folder, but then they must remember to do that, and remember to keep doing it, and it’s still painful to trawl through at any point down the line.

Option C: “My PLM system has a 3D viewer!”

You might think the solution to this lies in the fact that SOLIDWORKS Manage or 3DEXPERIENCE claim to have 3D viewers that even allow markup. We were still using ENOVIA when I was last drawing parts, but having been demoed a few of the newer iterations of these tools, I can say that all that I’ve seen so far have been incredibly disappointing.

Packaging up a Snipping Tool knock-off and putting a button for it in your toolbar is not providing a 3D review process. It’s just the PowerPoint screenshot ping-pong review process that happens to be accessed from your PLM.

This should be short and sweet:

Pros

- It’s sort of convenient, I guess?

Cons

- See Option B.

For what it’s worth, I do think it’s pretty unforgivable that the CAx oligopoly has been so slow to provide good functionality here. Onshape seem to be on top of it, and I don’t have much exposure to the Siemens stack, but if you own everything from geometry constraint system kernel through to the PLM, then you should be able to do better than this.

Option D: Something different

This is where we come in—and there are also a couple of other startups playing in the space, so hopefully you’ll start to see more of the ‘something different’ approach in the near future.

In our case, we wanted a tool that:

- Provides centralised, asynchronous, remote review functionality.

- Allows for the design to be reviewed in 3D, with the ability to explore and interact with the model.

- Includes a mechanism for recording feedback in context, and for immediately making that feedback visible to the designer and any other interested parties.

- Provides clear traceability of the design’s evolution, and of the feedback provided at each stage.

- Doesn’t require the installation of any additional software.

Practically, this means we needed to be able to:

- Run in a web browser.

- Ingest CAD data at discrete points in the design process.

- Process that CAD data such that it can be rendered.

- Allow users to view and interact with the rendered model.

- Allow users to toggle between a perspective and orthographic/parallel projection; see cameras and projections.

- Allow users to annotate the model, providing contextualised feedback.

Enter Three.js

Anneal is a web-based platform, so we’re already running in a browser. We can also already ingest user uploads, with these being encrypted and stored in a customer-specific object store.

That really just left processing, display, and annotation. To address these, we built:

- A server-side processing pipeline that can process STEP and STEP assembly data into a more readily renderable format.

- A Three.js based viewer.

- Our own annotation functionality on top of that.

Our processing pipeline and annotation functionality are out of scope here, so let’s stick to the Three.js viewer, and how you can coax some nice behaviour out of it.

There are plenty of guides to using Three.js out there, so I’m going to work on the assumption that you’ve got some stuff ready to render and you’ve put together a basic scene. If you haven’t, then I’d recommend starting with the docs.

A primer on 3D graphics

Once you’ve got some data that’s capable of being rendered, you need to think more about how you want to present it to the user. This is where some basic 3D graphics concepts and high school trigonometry come in handy.

Cameras and projections

In 3D graphics, the camera is the point from which the scene is viewed; it determines what the viewer sees and how they see it—effectively dictating how the 3D scene is projected onto a 2D screen.

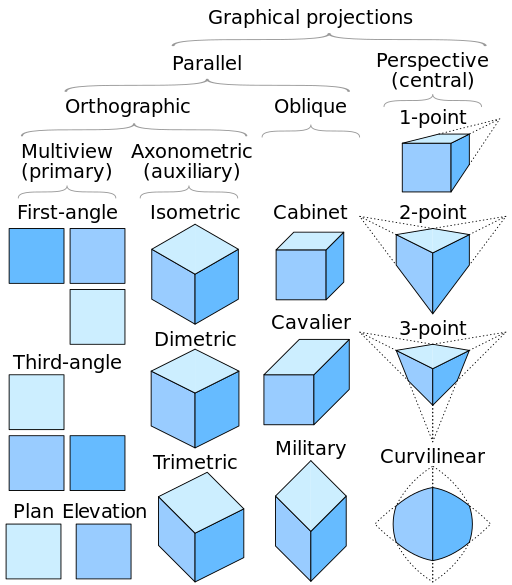

There are two camera types that are commonly used in this context: perspective and orthographic.

Perspective projection is designed to mimic the way in which the human eye perceives the world. In this projection, objects appear smaller as they move further away from the viewer, creating a depth effect that helps create a sense of scale within the scene. Perspective projection is the default choice for anything you would wish to present to the user with realistic proportions: video games, public-facing product renders, special effects, etc.

Credit: Hat Trick Productions / Channel 4

In contrast, orthographic projection ignores the effects of perspective. Objects in orthographic projection retain their size and shape regardless of their distance from the viewer. This means there’s no foreshortening, and parallel lines in the scene remain parallel in the rendered image.

Orthographic projection is particularly useful in technical and engineering applications, where accurate and undistorted measurements tend to be important. It’s widely employed in CAD programs, which is probably the only place you’d ever really see it in use—though many will have also seen isometric illustrations, which are a form of orthographic projection.

Here’s a nice illustration of projection types:

Credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Cmglee

Each of those you see in the axonometric projection column will be achievable in our viewer by manipulating the camera, provided it is set to use an orthographic projection.

Note:

Since this post is already incredibly long, I’m going to stick to the perspective camera for now, and leave the rest for another time. Apologies to anyone who’s reading this while building similar engineering-focused tools—a lot of the work in building a slick implementation for that use-case really relates to how seamless transitions between orthographic and perspective projections can be achieved.

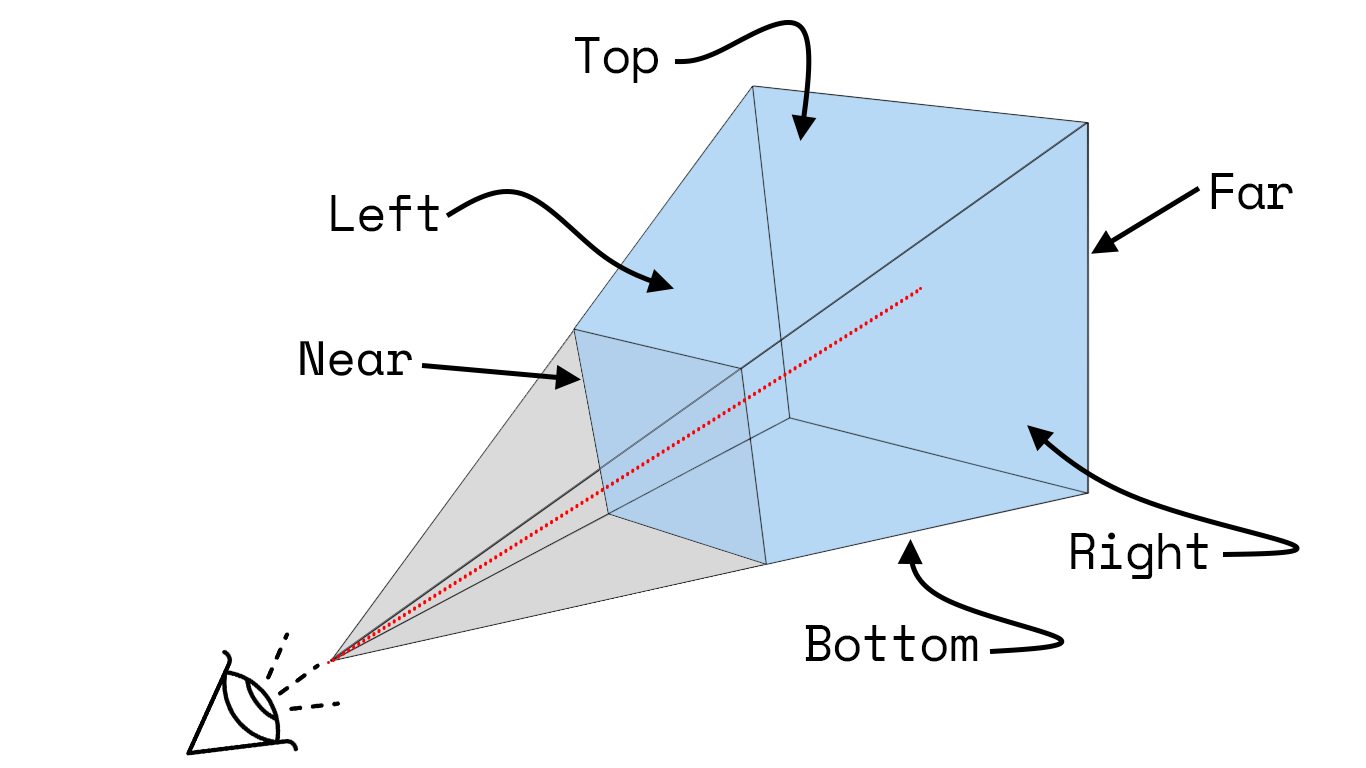

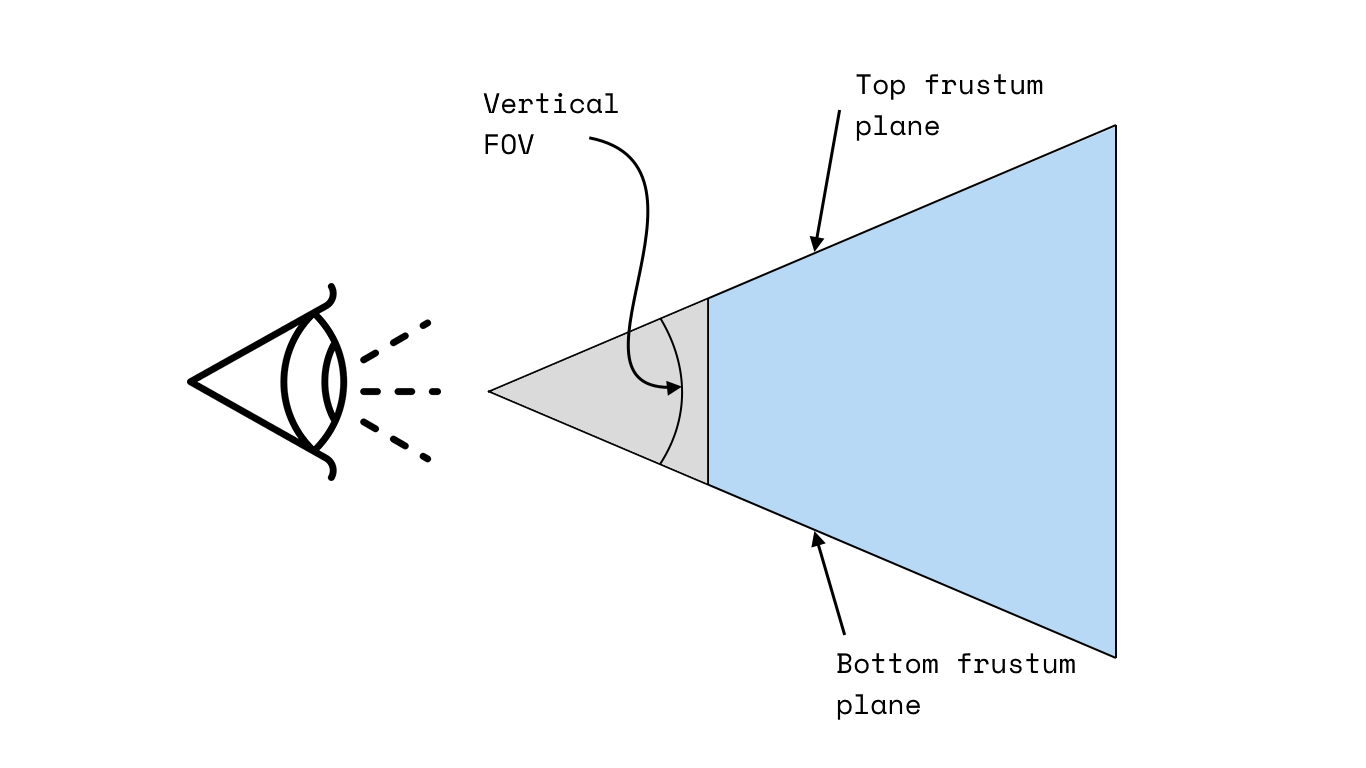

View frustums

The view frustum is the volume of space that is visible to the camera. In the case of a perspective camera, it’s effectively an imaginary, truncated pyramid sitting somewhere in 3D space. It is defined by:

- A set of four angled planes/panels that form a shape akin to a pyramid with its top lopped off. If you were to extend

these planes such that their edges converged, they would form the intersecting, lateral faces of a pyramid whose apex

sits at the camera position.

- These are referred to as the left, right, top, and bottom planes.

- A set of two planes, both parallel to the imaginary pyramid’s base and lying perpendicular to a line struck from the

camera through its target, that intersect with the pyramid—cutting it to leave the frustum portion.

- These two parallel planes, referred to as the near and far planes, define the depth of the view frustum.

Here’s a diagram I put together to illustrate this:

The vector along which the camera is looking is shown in red, the frustum in blue, and the remainder of the imaginary pyramid in grey.

Field of view

Another concept worth mentioning here is the field of view (FOV). This could refer to one of two things: the angle between the left and right planes, known as horizontal FOV, or the angle between the top and bottom planes, known as vertical FOV. In Three.js, we specify vertical FOV, then effectively compute horizontal FOV from vertical FOV and specified aspect ratio.

Taking a side elevation of our diagram above, we can see that the vertical FOV is just the angle between the top and bottom planes.

Our aspect ratio we can compute later, once we know the dimensions of the element we’ll be rendering in.

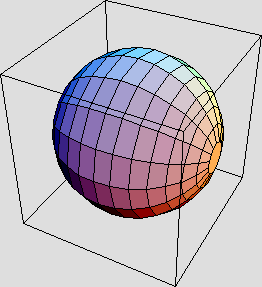

Bounding boxes and bounding spheres

These concepts are much simpler to explain than the view frustum and will be useful when we actually get around to parameterising things.

In 3D, a bounding box is simply the smallest possible axis aligned cuboid that can contain the given object. Axis aligned just means that the box’s edges are parallel to the coordinate axes of the scene—so you can’t sneakily rotate your bounding box cf. the axes to minimise its volume.

Credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Cobra w

In Three.js, a bounding box is described by two Vector3 objects:

min and max. As I think about it, the min vector describes the coordinates of the box’s lower-left-front corner,

and the max vector describes the coordinates of the box’s upper-right-back corner.

You could also imagine numbering each of the box’s eight vertices, pulling together the coordinates of each, then taking the minimum and maximum for each of your sets of x, y, and z values:

Similarly, a bounding sphere is simply the smallest possible sphere that can wholly enclose the target object or group of objects.

In our case, we derive our bounding sphere from the bounding box. Its centre will lie at the midpoint of the bounding

box’s min to max diagonal, and its radius will be half the length of that diagonal. This means the bounding sphere’s

surface will be also coincident with each of the bounding box’s eight vertices—neatly wrapping around the box.

Viewer setup

Having covered projections, frustums, and bounding boxes, we can put that information together to set up our viewer. Our basic ambition is to create a camera, configure it appropriately, set its position somewhere reasonable, then point it at the centre of our scene.

After that we can think about controls, and how we want the user to be able to interact with the scene.

1: Camera creation

This is the easiest bit, and sample code is available from various sources online. We’ll create a scene, load in some data, then set up a camera and a renderer.

...

// Create scene.

this.scene = new THREE.Scene();

// Load file. Note that this method handles file retrieval and processing,

// then handles the addition of the relevant geometry to the scene.

await this.loadFile();

// Create renderer. Uses our threeHelper module.

this.renderer = threeHelper.createRenderer();

this.viewerContainer.appendChild(this.renderer.domElement);

// Create camera.

this.perspectiveCamera = new THREE.PerspectiveCamera();

...

The relevant threeHelper functions are as follows:

function createRenderer() {

const renderer = new THREE.WebGLRenderer({ antialias: true, alpha: true });

renderer.shadowMap.enabled = true;

renderer.shadowMap.type = THREE.PCFSoftShadowMap;

renderer.autoClear = false;

return renderer;

}

As a quick snippet of the sort of thing your loadFile method might want to actually do, here’s an example that would

generate both a surface mesh and a wireframe mesh for a given geometry:

...

const material = new THREE.MeshPhongMaterial({

color: constants.DEFAULT_COLOR,

wireframe: false,

side: THREE.DoubleSide,

});

const wireframeMaterial = new THREE.MeshBasicMaterial({

color: constants.WIREFRAME_COLOR,

wireframe: true,

transparent: true,

opacity: constants.WIREFRAME_OPACITY,

side: THREE.DoubleSide,

});

const mesh = new THREE.Mesh(geometry, material);

const wireframe = new THREE.Mesh(geometry, wireframeMaterial);

this.meshGroup = new THREE.Group();

this.meshGroup.add(mesh);

this.meshGroup.add(wireframe);

...

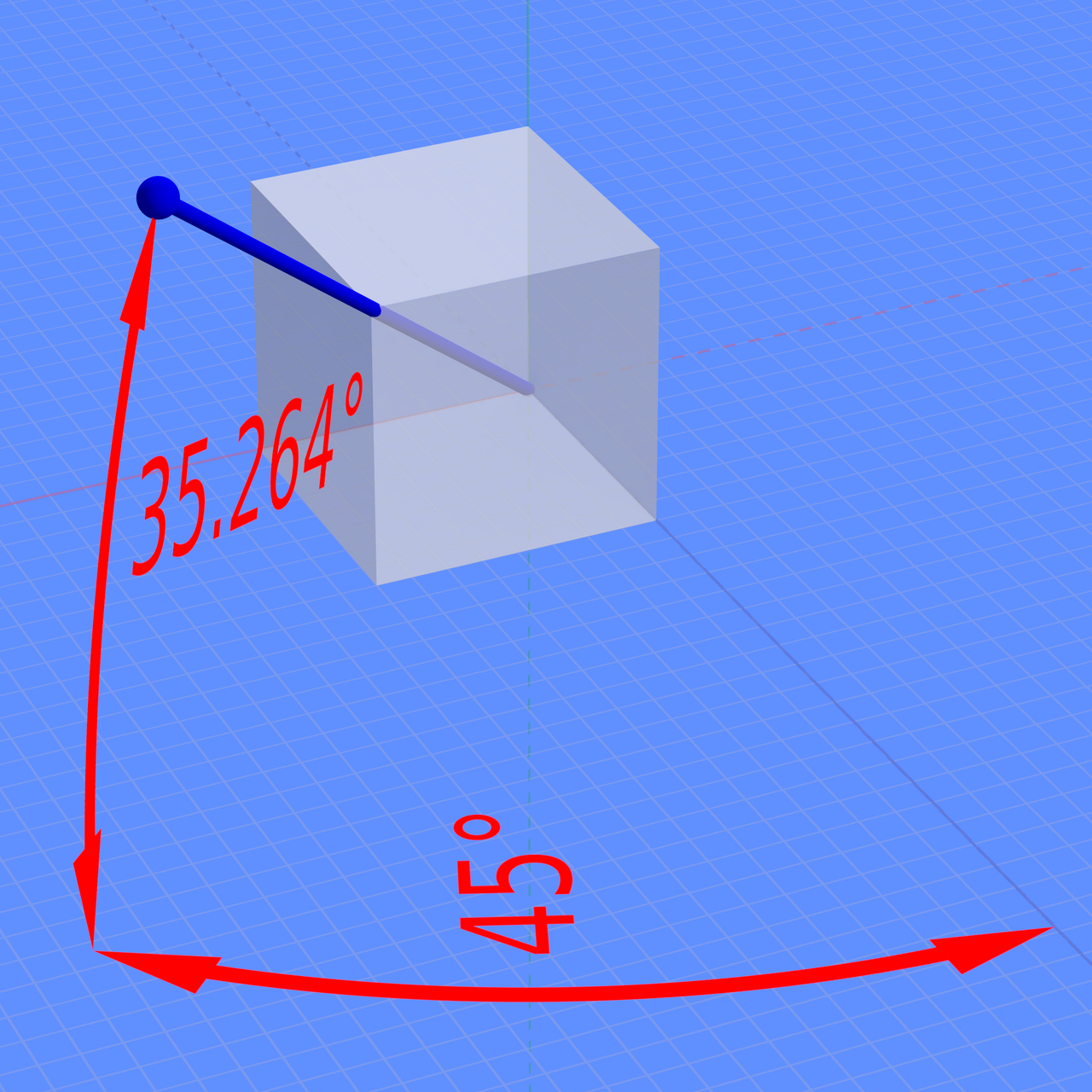

2: Camera position and configuration

Once you’ve created the scene, rendered some geometry, and created a camera, you’ll need to place and configure the thing.

I keep a set of constants defined to go with our viewer component, and some of these relate to camera configuration:

...

const HOME_AZIMUTH = 45; // Isometric.

const HOME_ELEVATION = 35.264; // Isometric: atan(1/(sqrt(2)).

const PHI_FOV = 45; // FOV, degrees.

const ZOOM_SCALAR = 1.5;

...

Working through these in order:

HOME_AZIMUTHandHOME_ELEVATIONrelate to the default (home) camera position. Three.js uses y-up, so these are the angles, in degrees, that the camera will be rotated around the x and y axes respectively. In our case, we’ve set these to correspond to the default position from which an isometric view is drawn, but you could set them to anything you like. The figure below provides a clear illustration of what these angles mean.PHI_FOV: This is the vertical FOV, in degrees. The default is 50°, but we’ve been running with 45° for a while now, and it seems to work well. Once we’ve accounted for this parameter in some downstream calcs, a higher value will give you wider field of view—more like a fisheye lens—and a lower value will give you a narrower field of view—more like a telephoto lens.ZOOM_SCALAR: This is a scalar that we apply to determine the camera’s initial distance from the centre of the scene. We first compute the distance required to fit the entire scene in frame, then scale it by this value. I’ve found 1.5 to provide a good balance between being close enough to the scene to see detail, and far enough away to see the whole thing without first having to zoom out.

Credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Datumizer

Though we could set some initial properties on the camera at this point, particularly those related to the FOV, let’s rattle through the rest of the maths and get all the values we need.

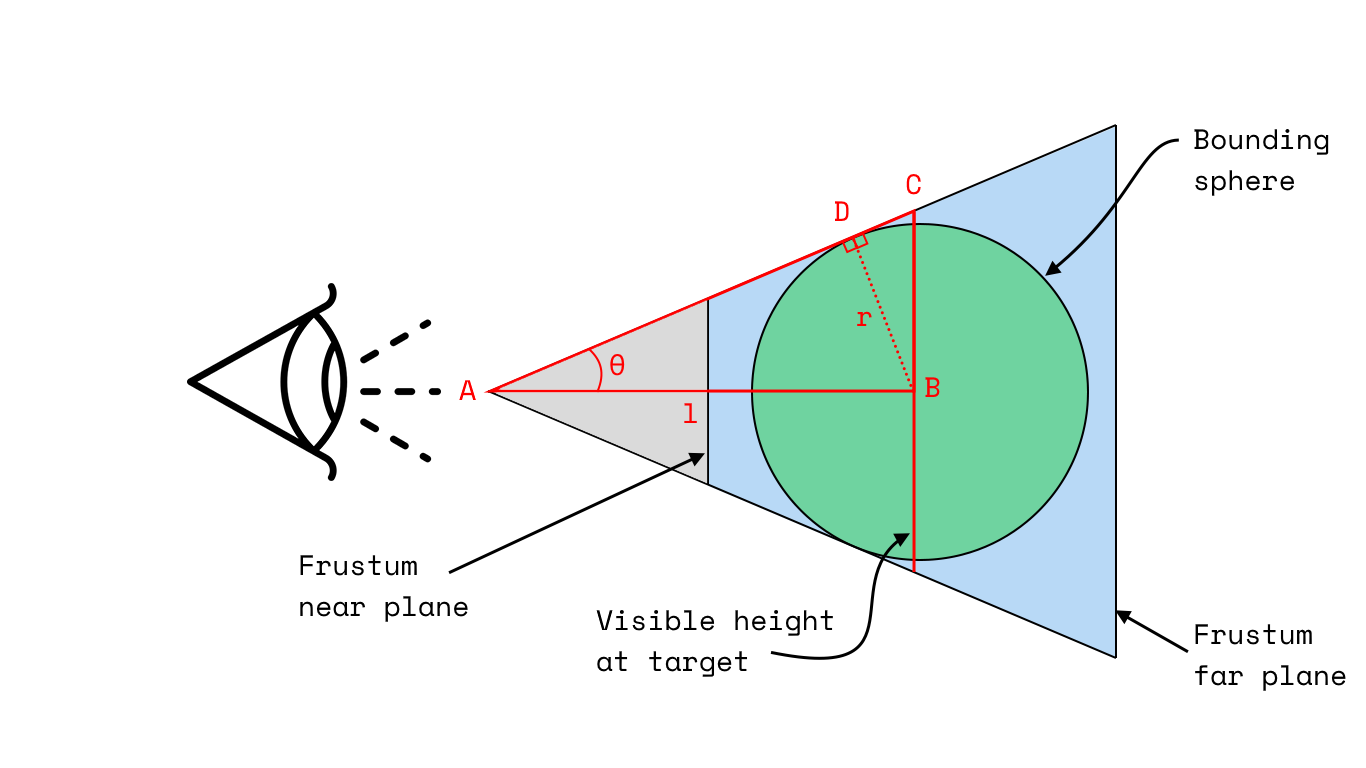

2.1 Raw camera distance from centre of scene

The hardest part here is computing the distance from the camera to the centre of the scene, which I’ll call $l$. To help illustrate what we’re after, here’s a marked upside view of our frustum:

Some parameters on here we know already, others we will have to compute.

Our objective is to compute $l$, the distance from the camera to the centre of the scene. We know the following:

- $\theta$: Half the vertical FOV. We can compute this from our

PHI_FOVconstant, where $\theta = \frac{\phi}{2}$. - $r$: The radius of the bounding sphere for our geometry. Once we’ve got some data rendered, we can have Three.js generate our bounding box and, from that, our bounding sphere.

Given that we want to compute $l$, you should be able to simply consider the triangle $ABD$ and see that:

However, in the interest of making downstream parallel/perspective toggle calculations easier to work with, we do this in a slightly more convoluted way:

- Using our bounding sphere radius, $r$, and our half vertical FOV, $\theta$, we compute the visible height in the target plane—which is parallel to both our near and far planes, but intersects with the centre of our bounding sphere.

- We then compute the distance from the camera to the centre of the bounding sphere, $l$, using the visible height and the half vertical FOV, $\theta$.

This requires a little bit of high school trigonometry, but ultimately looks like this:

Giving $BC$ the handier name $h$, we can then compute $l$ as follows:

$$ l = \frac{h}{\tan(\theta)} $$

This leaves us with both visible height and distance to camera parameters that are useful when we want to toggle between projections.

The code for this is along these lines:

export function deg2rad(angle: number): number {

return (angle * Math.PI) / 180;

}

export function computeVisibleHeightFromAngleAndRadius(phiFov: number, radius: number): number {

// Calculate visible height of the object.

const thetaFov = phiFov / 2;

const thetaRad = deg2rad(thetaFov);

const visibleHalfHeight = radius / Math.cos(thetaRad);

const visibleHeight = 2 * visibleHalfHeight;

return visibleHeight;

}

export function calculateDistanceFromAngleAndHeight(phiFov: number, visibleHeight: number): number {

// Calculate distance from camera to center of a bounding sphere.

// Note that visible height will be larger than sphere diameter, as produced

// by computeVisibleHeightFromAngleAndRadius, and phi is full

// included vertical FOV angle.

//

// |----visible height-----|

// |-----h-----|

// \ | /

// \ | /

// \ | /

// \ l | /

// \ | /

// \ | /

// \ | /

// \ | θ /

// \ | /

// \ | /

// \|/

// camera

//

const thetaFov = phiFov / 2;

const thetaRad = deg2rad(thetaFov);

const h = visibleHeight / 2;

const l = h / Math.tan(thetaRad);

return l;

}

2.2 Camera position

Now that we know how far the camera needs to be from the centre of the scene in order to accommodate the entirety of our

bounding sphere, we can set its position. This is fairly straightforward: we just scale our $l$ value by our

ZOOM_SCALAR constant, then set the camera’s position to be that distance from the centre of the scene—at whatever

angles we’ve specified in our HOME_AZIMUTH and HOME_ELEVATION values.

To facilitate this, we define a utility Coordinate type and a function to convert from spherical to Cartesian

coordinates:

type Coordinate = {

x: number;

y: number;

z: number;

};

export function convertToCartesian(azimuth: number, elevation: number, distance: number): Coordinate {

// Convert azimuth and elevation to radians.

const azimuthRad = deg2rad(azimuth);

const elevationRad = deg2rad(elevation);

// Calculate the x, y, and z coordinates using spherical coordinates formula.

const x = distance * Math.cos(elevationRad) * Math.sin(azimuthRad);

const z = distance * Math.cos(elevationRad) * Math.cos(azimuthRad);

const y = distance * Math.sin(elevationRad);

return { x, y, z };

}

Then, to actually compute the coordinates of our desired camera position, we do the following:

....

// Calculate distance from camera to center of bounding sphere (including scaling).

const r = objectRadius;

const height = computeVisibleHeightFromAngleAndRadius(phiFov, r);

const l = calculateDistanceFromAngleAndHeight(phiFov, height) * zoomScalar;

// Get coords for camera, offset from box center.

const coords = convertToCartesian(azimuth, elevation, l);

const x = coords.x + objectCenter.x;

const y = coords.y + objectCenter.y;

const z = coords.z + objectCenter.z;

...

Note that our variable names are slightly different here as we’re working within a function that’s intended to be

reusable, so our ZOOM_SCALAR, HOME_AZIMUTH, and HOME_ELEVATION constants are simply passed in as arguments.

2.3 Remaining camera configuration

Once we’ve determined the desired camera position, all that really remains is to set the position of the camera’s near and far frustum planes. For this, we need a few more constants, then some straightforward maths.

Our constants are as follows:

const X_FAR_SCALAR = 5;

const X_NEAR_SCALAR = 0.05;

const X_NEAR_DEFAULT = 0.1;

These represent:

X_FAR_SCALAR: A scalar that we apply to the distance from the camera to the ‘back’ of the scene. This gives us a significant margin, and ensures that the far plane is always further away than the furthest part of the scene.X_NEAR_SCALAR: A scalar that we apply to the distance from the camera to the ‘front’ of the scene. Again, gives us some margin, and ensures that the near plane is always close to the camera the nearest part of the scene.X_NEAR_DEFAULT: The default distance from the centre of the scene to the near plane. Whichever is smaller, this or the value computed usingX_NEAR_SCALAR, will be used as the near plane distance.

In the case of the far plane, we know the distance to the sphere’s furthest point will be the distance from the camera to its centre plus its radius: $l + r$.

For the near plane, we know the distance to the sphere’s nearest point will be the distance from the camera to its centre minus its radius: $l - r$.

Applying our scaling and, in the case of the near plane, taking the minimum of the scaled value and our default value, we need:

Where:

In code, this looks like:

// Handle frustum calcs.

const far = (l + r) * X_FAR_SCALAR; // Distance to back of scene, scaled.

const near = Math.min((l - r) * X_NEAR_SCALAR, X_NEAR_DEFAULT);

2.4 Putting it all together

Putting all of that together, we have a pair of functions that compute initial camera setup parameters:

export function computeDefaultCameraPosition(

phiFov: number,

objectRadius: number,

objectCenter: Coordinate,

azimuth: number,

elevation: number,

zoomScalar: number

): {

position: Coordinate;

l: number;

} {

// Calculate distance from camera to center of bounding sphere (including scaling).

const r = objectRadius;

const height = computeVisibleHeightFromAngleAndRadius(phiFov, r);

const l = calculateDistanceFromAngleAndHeight(phiFov, height) * zoomScalar;

// Get coords for camera, offset from box center.

const coords = convertToCartesian(azimuth, elevation, l);

const x = coords.x + objectCenter.x;

const y = coords.y + objectCenter.y;

const z = coords.z + objectCenter.z;

const position = { x, y, z };

return { position, l };

}

export function computeDefaultPerspectiveCameraFrustum(

objectRadius: number,

cameraDistanceFromTarget: number

): {

near: number;

far: number;

} {

const r = objectRadius;

const l = cameraDistanceFromTarget; // From camera to center of bounding sphere.

// Handle frustum calcs.

const far = (l + r) * X_FAR_SCALAR; // Distance to back of scene, scaled.

const near = Math.min((l - r) * X_NEAR_SCALAR, X_NEAR_DEFAULT);

return { near, far };

}

This is called from our viewer component using the constants we outlined above.

setDefaultCameraPosition(camera, controls) {

camera.position.set(

this.defaultCameraPosition.x,

this.defaultCameraPosition.y,

this.defaultCameraPosition.z

);

controls.target.set(constants.ORIGIN.x, constants.ORIGIN.y, constants.ORIGIN.z);

controls.update();

camera.updateProjectionMatrix();

},

setDefaultPerspectiveCameraFrustum() {

const params = Geometry.computeDefaultPerspectiveCameraFrustum(

this.boundingSphere.radius,

this.defaultCameraDistanceFromTarget

);

const { clientWidth, clientHeight } = this.viewerContainer;

const aspect = clientWidth / clientHeight;

this.perspectiveCamera.fov = constants.PHI_FOV;

this.perspectiveCamera.aspect = aspect;

this.perspectiveCamera.near = params.near;

this.perspectiveCamera.far = params.far;

}

3: Controls

In our case, we set up simple orbit controls that allow

the user to rotate the camera around the scene, and to zoom in and out. These are pretty straightforward to set up, and

we by default point ours at the scene origin: 0, 0, 0.

// Create controls.

this.perspectiveControls = threeHelper.createOrbitControls(this.perspectiveCamera, this.renderer.domElement, true);

The relevant threeHelper functions are as follows:

function createOrbitControls(camera, rendererElement, enabled) {

const controls = new OrbitControls(camera, rendererElement);

controls.enableDamping = true;

controls.dampingFactor = constants.CONTROL_DAMPING_FACTOR;

controls.screenSpacePanning = true;

controls.enabled = enabled;

return controls;

}

Limitations

The most obvious limitation in what is outlined here really relates to what we point the camera at by default. Though

our computeDefaultPerspectiveCameraParameters function accounts for the bounding sphere’s centre, our orbit controls

and what the camera actually looks at defaults to the scene origin. For parts that are small and centered well away from

the origin, this can mean the camera basically points at empty space and the user has to manually reorient the camera to

see the part.

Further work

In the interest of keeping this post no longer than it already is, I’m going to wrap it up here—but the outstanding bits and pieces that I’ve added to make the viewer work nicely are:

- A mechanism for toggling between orthographic and perspective projections.

- A grid on the ground plane.

- A view cube style axes helper.

- A quick ‘return to home’ button that resets the view.

- An unfolded cube widget that can be used to orient the camera parallel to a given face.

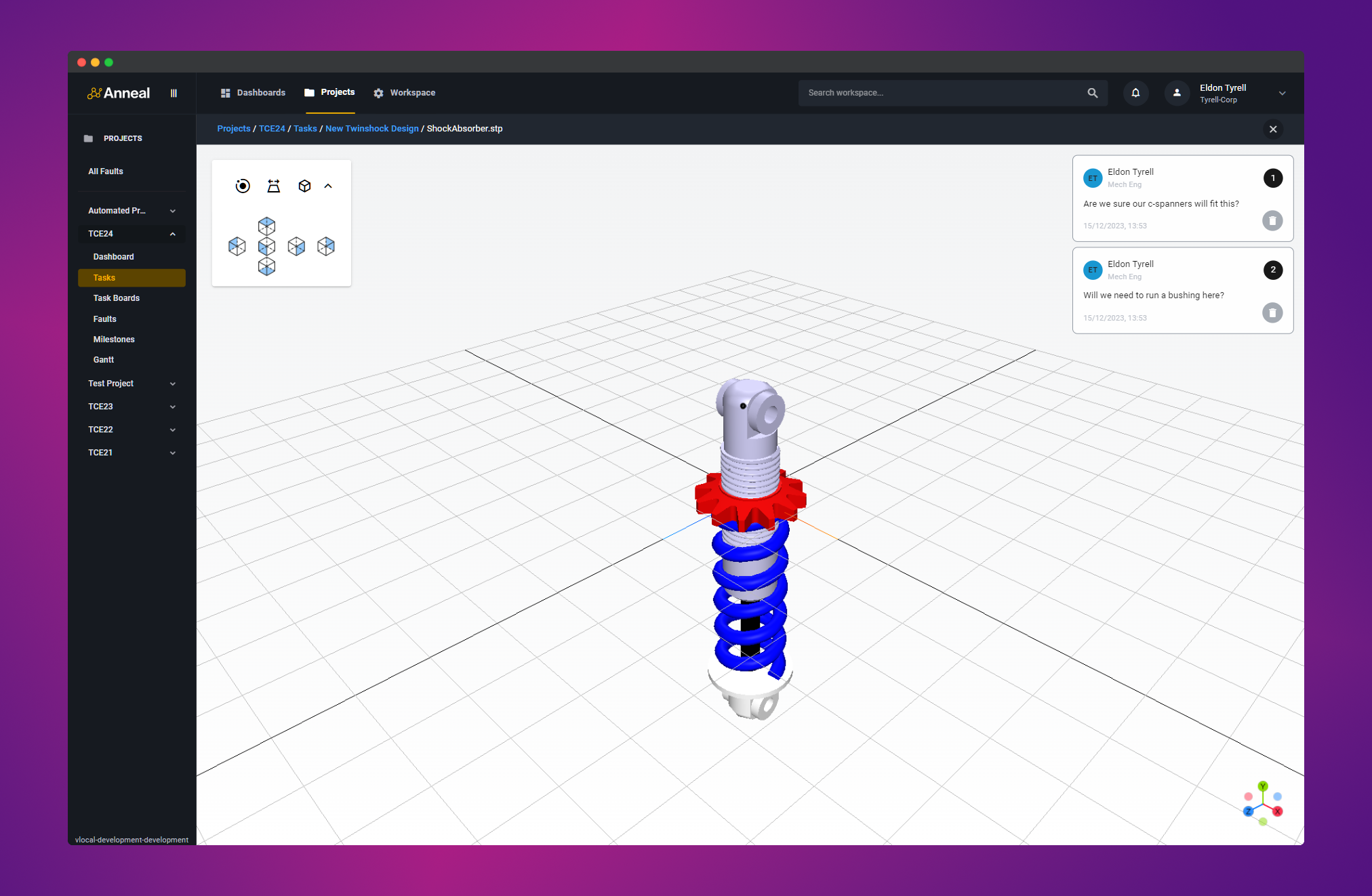

The result

There are some demo videos on our LinkedIn, but here’s a screenshot of the viewer in action—including items listed in further work.

https://www.getanneal.com

Spotted any gaffes? Got any questions? Please get in touch!